This is the second lecture about the Douro Valley by the great viticulturist António Magalhães. Today’s theme goes literally beneath the surface. After exploring the climate in our first session, we turn to the second pillar of the region’s terroir: its soil.

A Soil Made by Hand

When you walk through a vineyard in the Douro Valley, take a moment to look down. You see the slow artistry of nature, which over millions of years created the schist beneath your feet, and the tireless toil of generations who transformed it into living soil where vines can thrive.

The Douro’s deep valleys were carved over millennia by the river and its tributaries. On those steep slopes, the native soils, known as leptosols, are little more than a palm’s depth of earth resting on hard schist. Left untouched, they would never have sustained flourishing vines.

But in the Douro, people refused to accept nature’s limits. Over the course of centuries, they created anthrosols — soils made by human hands. The locals call the act saibrar, agronomists surribar: it means breaking rock to create soil where vineyards can grow.

The photograph shows that the schist bedrock appears brittle and easily broken. Above it lies the soil created by human labor. Look closely, and you can see the vine roots reaching down, searching for that last drop of water that keeps them alive through the scorching summer heat.

The image illustrates the words of the Marquis of Villa Maior, from his 1875 treatise, Practical Viticulture:

“The longevity of the Douro and Burgundy vines is due to the extraordinary development of their roots, favored by the nature of the subsoil.”

Breaking Rock to Grow Life

Until the late 19th century, surribar was done with nothing more than pickaxes and iron bars. In the 20th century, dynamite was introduced, followed later by bulldozers and hydraulic excavators. Yet the goal remained the same: to give each vine at least a meter and a half of soil depth.

The schist fractures almost vertically, allowing roots to slip deep between its plates. There, the vine finds not abundance but balance: less than 1.5 percent organic matter, yet perfectly aerated and rich in minerals. These fractured layers also ensure excellent drainage, carrying away excess rainwater while retaining just enough moisture for the vines to endure the long dry season. It is a poor soil that yields noble fruit, a reminder that in wine, perhaps as in life, struggle builds character.

Stones and Gravel

Kneel in a Douro vineyard and you’ll see a glittering mosaic of crushed stone and gravel. To outsiders, it looks barren; to the vines, it’s paradise.

In 1947, agronomist Álvaro Moreira da Fonseca, who devised the Douro’s vineyard classification, ranked soils by their gravel content. His creed, simple and enduring, can be expressed in words worthy of being carved in stone: “Vines thrive on stony ground.”

The gravel plays alchemy with the elements: reflecting sunlight by day, releasing heat by night, regulating the vine’s rhythm. It stores warmth, tempers vigor, and transforms scarcity into intensity.

Counting by the Thousands

António says that “The poorer the soil, the closer the vines.” Douro farmers compensate for the soil’s low fertility by planting vines at higher densities. Each vine produces modestly, but together they create abundance. Instead of counting hectares, growers speak of milheiros — groups of a thousand vines.

After the phylloxera epidemic, the rebuilt terraces — socalcos — reached a density of 6.5 milheiros per hectare, enough to make every meter of stone wall worthwhile.

Sculpting the Mountain

Rain, the same force that helped carve the Douro, also threatens to destroy it. The solution lies in building terraces to prevent soil from sliding away. During the surriba, the stones brought to the surface are removed and reused to build the vineyard walls. This operation, called despedrega, is a practice that makes the back-breaking labor of surribar more rewarding.

Some of the terraces devastated by phylloxera were never replanted. Many owners, overcome with despair, abandoned the region to rebuild their lives elsewhere. Others chose to start anew, replanting vines on gentler slopes with more forgiving soils and milder climates.

These abandoned terraces, known as mortórios, have been reclaimed by the Mediterranean forest. Their stone walls, now entwined with wild vegetation, stand as silent witnesses to a tragic chapter in the Douro’s history.

The oldest terraces, built after phylloxera, were supported by dry-stone walls, feats of balance and beauty where each stone rests “one upon two.” In the 1960s, as labor became scarce and tractors arrived, new earth-banked terraces (patamares), depicted below, took their place — practical but less graceful.

At the turn of this century, António Magalhães and David Guimaraens, the head winemaker of Taylor’s Fladgate, combined the beauty of the old dry-stone terraces with the practicality of the modern earth-banked ones. Inspired by California’s Benziger Family Winery, they built narrow terraces, just 1.5 meters wide, each with a single vine row and a gentle 3 percent slope to drain rainwater safely. Precision-leveled by laser, this innovation protects against erosion while preserving the Douro’s graceful geometry.

Root and Rock

The phylloxera plague that ravaged European vineyards in the late nineteenth century arrived at the Douro in 1863-64.

Salvation only came after Jules-Émile Planchon, a French botanist, and Charles Valentine Riley, an American entomologist, discovered that grafting European grapevines (Vitis vinifera) onto American rootstocks could save the vines.

One such rootstock, Rupestris du Lot, thrived on the Douro’s poor, dry, schistous hillsides.

It seems to facilitate potassium absorption. This mineral helps regulate the opening and closing of tiny pores on leaves, called stomata, which control transpiration and CO₂ uptake — both essential to photosynthesis.

For decades, the Rupestris du Lot anchored the valley’s post-phylloxera vineyards, its deep-seeking roots echoing the surriba’s purpose: to connect life to stone. Even as newer, more productive hybrids replaced it, António continues to praise its quiet virtues — longevity, restraint, and resilience — the very qualities that define the Douro itself.

Granite Lagares

The granite lagares of the Douro are among the most enduring symbols of the region’s winemaking heritage. Their coarse surfaces help regulate temperature during fermentation and impart a tactile connection to the land — the sensation of grape skins and must mingling with the mineral essence of granite itself.

For centuries, blocks of rock were quarried from places like Vila Pouca de Aguiar, Portugal’s self-proclaimed “granite capital,” where the stone’s density allows it to be cut into large rectangular slabs.

António concludes his lecture with poetic words: “In the Douro where I grew up, the grapes journey from rock to rock — ripening in the heat of schist and fermenting in cool granite lagares.”

What to Visit

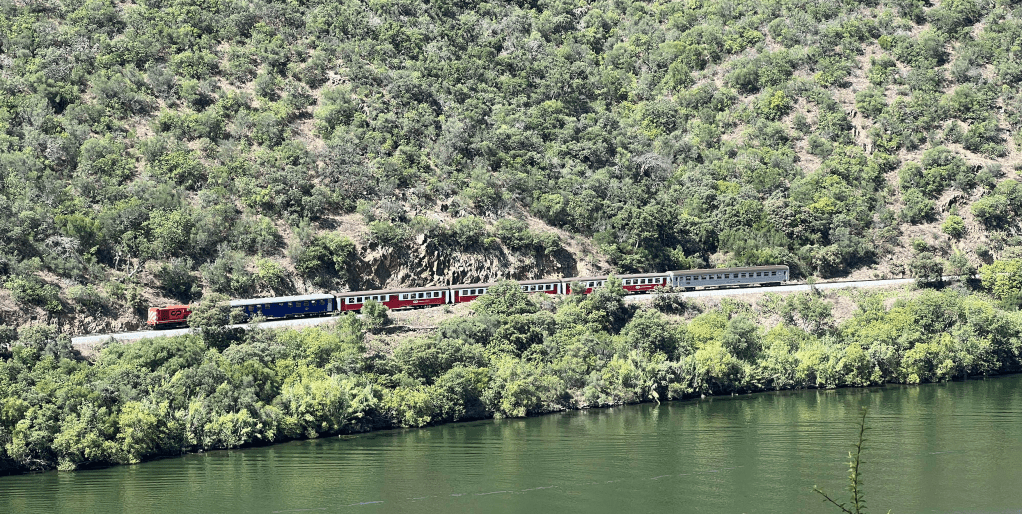

The train trip from Pinhão to Pocinho offers a geology lesson. Along the slopes that flank the railway, you see the leptosol with its thin layer of soil above the parent rock.

The art of building dry stone walls is beautifully explained at the Wine Museum in São João da Pesqueira, a town whose historic center also deserves exploration. The visit whets the appetite for lunch at Toca da Raposa, in Ervedosa do Douro, about 8 kilometers away along the National Road 222, heading toward the mouth of the Torto River — another magical tributary that shapes the wines of the Douro, alongside the Pinhão River. In the summer, you can also book an unforgettable picnic at the Foz Torto estate with our friend Abílio Tavares da Silva.

António recommends reading “Taste the Limestone: A Geologist Wanders Through the World of Wine,” by Alex Maltman. You’ll return home with a deeper understanding of soils and their decisive role in defining terroirs across the world.