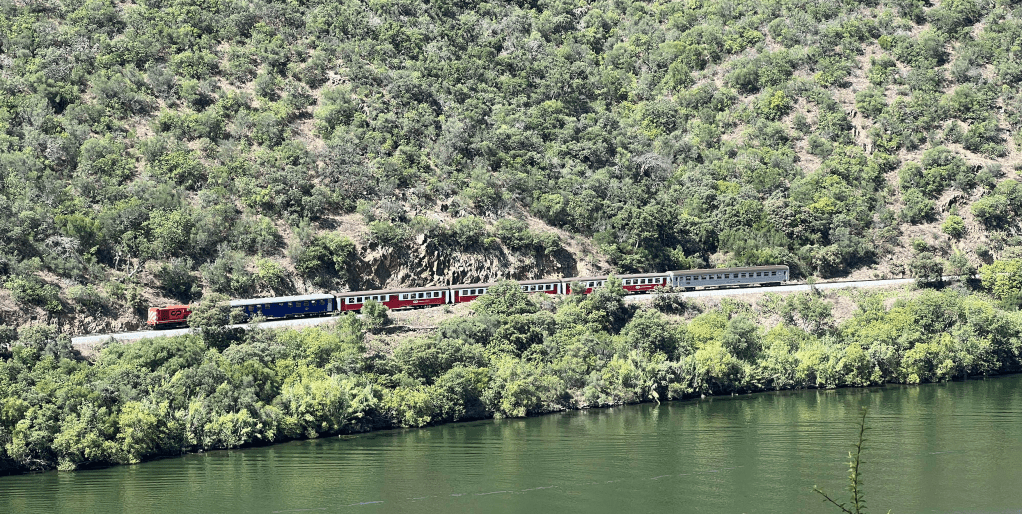

In this fifth masterclass with viticulturist António Magalhães, we follow the seasons in the Douro Valley. The lecture brings to mind a famous passage from the Book of Ecclesiastes: “To everything there is a season, and a time to every purpose under heaven.”

Each season brings its own tasks, anxieties, and rewards. Despite the vastness of the landscape, the work of tending vines remains a human craft, learned through experience and carried out with dirt under the nails and an eye on the sky.

António grew up with the notion that the agricultural year ran from November 1 to October 31. At Taylor Fladgate, where he worked for over three decades, the year was divided into quarters: dormancy from November to February, growth from March to June, and ripening from July to October.

This calendar aligns with the concept of growing degree days. Developed in the 1930s by Albert Winkler at the University of California, Davis, it links vine growth to cumulative temperatures above 10 °C over the growing season, conventionally defined as April 1 to October 31.

But António has been pondering what to do about October. Over the past few decades, most Douro grapes have been harvested by the end of September, with only a few straggling vineyards picked in the first days of October. This shift reflects climatic change and the Douro’s growing emphasis on table wines, known as DOC Douro. In the past, when all grapes were destined for Port, harvests came later to allow grapes to reach the deeper ripeness Port requires. Viticultural choices over recent decades have also contributed to earlier harvests, as growers planted fewer varieties, favored early-ripening grapes and rootstocks, and increased sun exposure.

António is therefore exploring a different viticultural calendar: dormancy from early October through the end of February, growth from early March through the end of June, and ripening from early July through the end of September. Uneven in length, these seasons are more closely attuned to the rhythms of nature as they now unfold.

The Dormancy Season

As soon as the grapes are harvested in September and early October, attention turns to the olive trees planted around the vineyards.

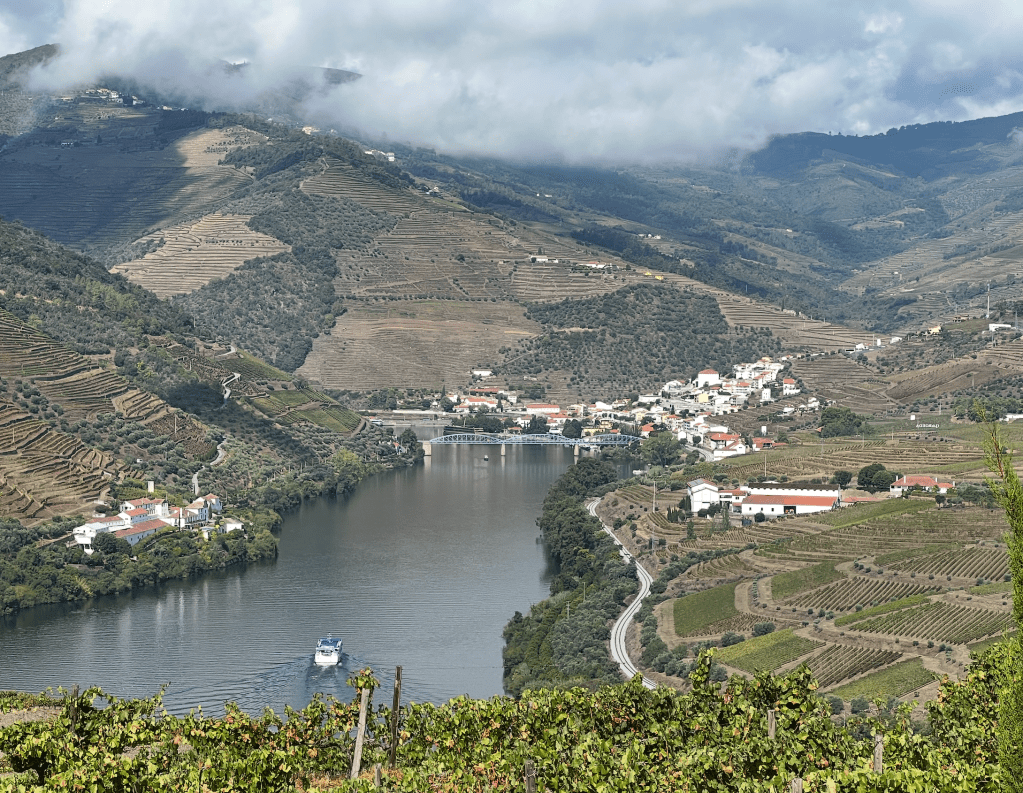

There is a natural complementarity between vines and olive trees. They draw water and nutrients from different soil depths, and their peak water needs occur at different times: vines in spring and early summer, olive trees in late summer and early autumn. Their distinct canopy structures mean they do not meaningfully compete for sunlight, and because their harvests follow one another, they do not compete for labor either.

In October, spontaneous vegetation awakens, washing the landscape in green. António likens the soil to a sideboard of drawers filled with seeds, opened selectively by the year’s weather. Fast-growing grasses help control erosion, while broad-leafed dicotyledons improve soil structure and biodiversity. Together, they form spontaneous mosaics in the fields, perhaps a model worth echoing in the vineyard, through field blends that create a mosaic of vines.

The vineyards are particularly spectacular in November. The leaves turn red and yellow, their rich palette reflecting the diversity of grape varieties.

During this period, farmers pray for rain to fill what António calls the “water piggy bank.” Because most vines, especially in the Baixo and Cima Corgo, are not irrigated, rainfall during dormancy is crucial: about 400 to 500 millimeters of water must be stored over these five months. Once reserves are replenished, cold temperatures are welcome: they keep the vines fully dormant, prevent premature budbreak, slow metabolic activity, reduce disease pressure, and ensure a synchronized, healthy awakening in spring.

Cold weather is also valuable in the cellar. Winemakers say that the cold “closes the color of the wine.” Traditionally, Port spent its first winter in the Douro Valley before being shipped to Gaia. In the past, the river’s powerful winter flow made navigation too dangerous; even after the Douro was tamed, producers continued the practice, having found it beneficial.

The dormancy season is a time for reflection in the vineyard and the cellar—on the year just past and the one to come. In the Douro, people say that after the harvest, “the wine must be allowed to speak.” Judgment is never rushed; wines are tasted and assessed only in January and February of the following year. At that point, samples of the most recent harvest are sent to the lodges in Gaia, where they are tasted alongside wines from the harvest two years earlier. This tasting is the beginning of a momentous decision that winemakers will make in March or April: whether the wine, now in its second year, is declared Vintage.

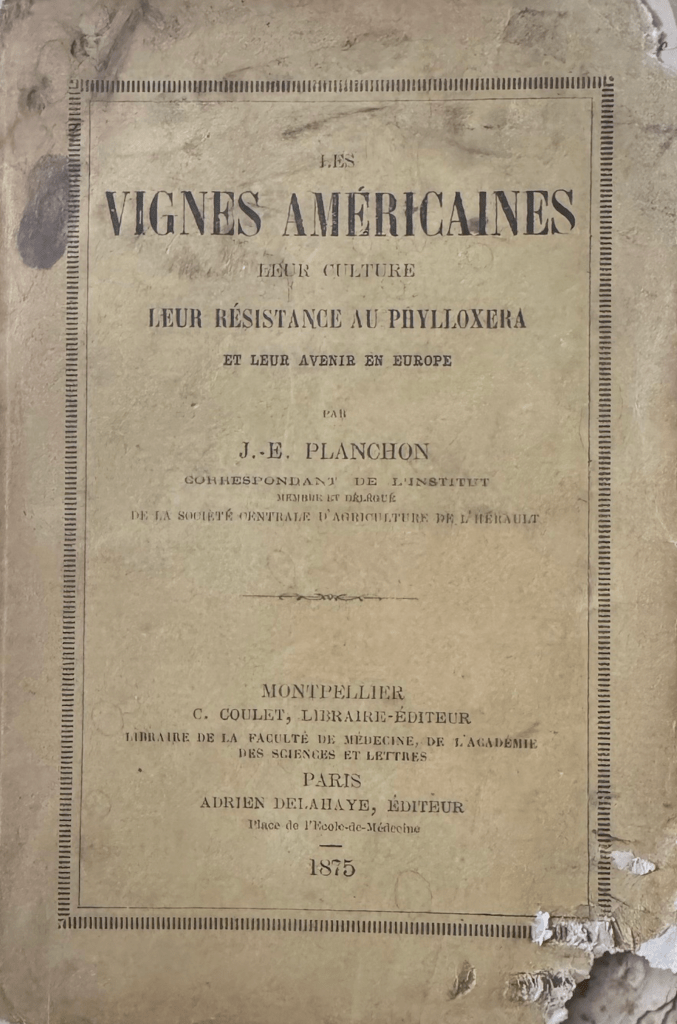

The most important task of the dormancy season is pruning. In the Douro Valley, vines behave very differently from one another, so each must be pruned individually. For this reason, the simple, efficient cordon system is avoided in favor of spur and cane pruning, also known as Guyot pruning, a method used in the Douro Valley long before Jules Guyot popularized it in the nineteenth century. This pruning method promotes vine rejuvenation, a vital practice in the Douro Valley.

Other winter tasks include maintaining the vineyards. Vines trained on vertical trellis systems require regular upkeep, and terrace walls must be repaired. In midwinter, dead vines are replaced, and new vineyards are planted.

The Growing Season

Vines grow from March to June. The first signs of phenological awakening are the flowering of Crepis spp, an herb with yellow blossoms that open only during the day, and a phenomenon known as “crying”: sap seeps from pruning cuts.

Budbreak (abrolhamento) soon follows, as the dormant buds left after winter pruning open to produce tiny shoots and leaves. In Pinhão, at the heart of the Douro Valley, budbreak typically occurs around March 14 or 15.

During the growing season, about 200 millimeters of rain are needed to support shoot development, leaf expansion, and canopy formation. As temperatures rise, the vines enter flowering, a brief and delicate phase when tiny, almost invisible blossoms appear on the clusters. Cold, rain, or wind can disrupt pollination, reduce fertility, and lead to irregular crops. For all our technological advances, flowering cannot be hurried or protected; it remains entirely at the mercy of the elements.

When flowering succeeds, fruit set follows—the moment when blossoms become tiny green grapes. This stage is fragile: poor weather can cause grape shatter, as flowers fall without forming berries, and a single gust of wind or cold front can reduce an entire hillside’s yield.

Vine growth must be monitored and guided along vegetation wires so that shoots form vertical hedges. Another key task is desladroamento, known in the Douro as despampa: the removal of shoots not selected during pruning, which would otherwise drain the vine’s energy and divert vigor from productive growth.

During the growing season, weeds must be removed in a narrow, 30-centimeter strip along the vine line, where they compete directly with the vine roots—preferably mechanically, and only as a last resort with herbicides.

Beyond this strip, weeds play an essential role. Ideally, these herbs are local and in balance, though that balance can be disrupted by herbicide use. Leguminous plants such as fava beans and red clover fix nitrogen in the soil, while other species prevent erosion, support microbial life, and attract beneficial insects—bees for pollination, and predators such as ladybugs and ground beetles that help control aphids, mites, and leafhoppers.

As the season advances, vines must also be protected from disease and pests. Powdery mildew (oidium) is a constant threat and is traditionally controlled with sulfur, a natural treatment used since the nineteenth century and one to which no resistance has developed. Downy mildew poses a growing threat: warmer temperatures have shortened its incubation period, increasing the number of infection cycles and narrowing the window for intervention. Copper is an effective fungicide against downy mildew; when mixed with lime and water as calda bordalesa, it also enhances the vine’s tolerance to drought.

Farmers must also contend with pests such as the cigarrinha-verde (green leafhopper, Empoasca vitis) and the traça-da-uva (grape moth, Lobesia botrana), whose presence varies from year to year. As we move from the Baixo Corgo toward the Douro Superior, grape moths become less common, while the green leafhopper becomes more widespread.

The Ripening Season

The ripening season runs from July to September. Through the long, dry Douro summer, berries develop under harsh conditions: heat waves can halt growth or cause dehydration, and skin-scorching sunlight is so common around St. John’s Day in late June that farmers call it “queima de São João” (St. John’s scorch). The steep schist terraces, magnificent as they are, offer little protection, leaving canopy management—carefully arranged leaves for shade—as the grower’s primary defense.

Veraison begins in July. Farmers say that “the painter has arrived” because grapes change color: reds turn from green to deep violet, whites become translucent and golden. But the stakes are high: if veraison is uneven, some berries ripen too early and others too late, complicating the harvest and compromising balance in the final wine.

After veraison, the clock starts ticking. With each passing day, grapes lose acidity and gain sugar, and the winemaker’s most consequential decision—when to harvest—comes into focus. The balance between freshness and sweetness must match the style of wine: DOC Douro table wines call for higher acidity, while Port is made by blending grapes naturally rich in acidity, harvested at full ripeness. One reason wine quality has improved over time is better harvest timing; in the past, grapes were often picked on predetermined dates, or when farmers’ children were available to help.

Theory suggests that the Douro’s many varieties ripen at different times; experience teaches otherwise. Despite their differences, they tend to converge on a single moment, as though the valley itself were whispering that the time has come.

Veraison is followed by three blessed weeks: the last week of July and the first two of August. Winemakers take a brief holiday to rest before the most demanding moment of the year: the harvest. Yet even away, the vines never leave their minds. Should the break be cut short? Is it time to return?

As this pause ends, growers return to their vigil among the vines. Some estates rely on laboratory measurements of sugar, acidity, and pH, but many Douro viticulturists, including those who taught António, trust another guide: intuition honed by daily practice. They walk the vineyards early in the morning, before the heat builds, gently crush a berry between thumb and forefinger, taste, and study the weather forecast. This quiet ritual tells them, often with surprising certainty, when the grapes are ready.

Mid-August is the most beautiful moment of the year. By then, the weeds have turned brown, forming a protective cover over the soil, while the vines take on a bright green hue that will gradually begin to fade.

All the work has been done, the harvest crews have not yet arrived, and the vineyards belong solely to the viticulturists. As harvest approaches, some varieties—such as Touriga Nacional and Tinta Roriz—grow dry and ungainly, while others, like Tinto Cão, retain their elegance. In a field blend, some vines wither, and others flourish, yet the ensemble always holds together.

Harvest in the Douro is both exhilarating and nerve-racking. Pick too early and the wine lacks depth; pick too late and it loses structure.

The ideal rainfall for September is modest—around 20 millimeters. A sudden downpour can swell berries, dilute flavors, or invite rot, but a light drizzle of 6 to 10 millimeters just before the harvest can refine the grapes. “How often we long for a gentle rain to settle the dust on the roads and wash the grapes before harvest,” says António.

That longing echoes throughout Douro history. Writing in 1788, John Croft observed that a little rain at harvest “fills the grapes, washes away the dust, and gives them greater freshness.” In 1912, Frank Yeatman of Taylor’s recalled how September thunderstorms at Vargellas saved grapes that summer heat had shriveled, before they gained sufficient sweetness. André Simon, in Port, tells a similar story about the legendary harvest of 1868: after an oppressively hot summer, J. R. Wright of Croft judged the grapes beyond hope, decided not to declare a Vintage year, and left for Porto. A timely, gentle rain proved him wrong, transforming the crop into one of the greatest Vintage Ports ever shipped—declared by every house except Croft.

Older growers say the greatest secret of the harvest lies not in what you pick, but in what you leave behind: quality depends on what you reject. Sorting, whether in the vineyard or at the winery, is an act of discipline. Imperfect clusters are left on the vine; sunburned berries are discarded. Only the healthiest fruit reaches the granite lagares. This simple yet demanding philosophy is one reason the Douro continues to produce some of the world’s most distinctive wines.