At the beginning of the last century, the German poet Rainer Maria Rilke wrote a series of letters to a young man who aspired to become a poet, urging patience, humility, and trust in the slow ripening of ideas.

In that spirit, we invited viticulturist António Magalhães to write a letter to a young Douro farmer. This eighth masterclass takes that form.

Peso da Régua, February 7, 2026

My dear colleague,

You asked me for advice on how to begin a life in the vineyards of the Douro Valley. I will try to answer simply, because in viticulture simplicity is often the most difficult achievement.

On tradition

First, understand that making great wine in a mountain region is never the work of a single lifetime. It is a relay race: you receive the vineyard, care for it as best you can, and pass it on to the next generation. You did not choose your starting point, and you will not see the finish line. This realization should make you both humble and demanding of yourself. Viticulture is the art of continuity: your vineyard must be able to thrive far into the future.

Learn from those who pruned your vines before you. In our profession, novelty is often overvalued. The vine breeder François Morisson-Couderc, successor to the great Georges Couderc, whose rootstocks helped rescue Europe’s vineyards after phylloxera, once said that a good idea in viticulture is one that remains a good idea twenty years later.

During the phylloxera crisis, Douro growers learned which sites to abandon and which never to plant at all. They set aside ill-adapted varieties such as Bastardo and Donzelinho Tinto, and created new ones, most notably Touriga Francesa, by crossing rustic, phylloxera-resistant Mourisco Tinto with Touriga Nacional, which the Baron Forrester called “the finest.” They also knew how to shape the post-phylloxera terraces, so that vineyards could once again thrive.

On respect

Unless your vineyard has a human scale that allows you to tend to it by yourself, you will have workers in your employ. Agricultural work is hard, and those who do it deserve our deep respect. Never ask anyone to perform a task without first explaining its purpose and why it matters.

Respect is owed not only to people, but also to the land.

On caring for the soil

Care for the soil by embracing organic viticulture. It is prudent to first gain experience on a small parcel. That is how, more than three decades ago, David Guimaraens, the head winemaker of Taylor Fladgate, and I took our first steps into organic viticulture, guided by David’s father, Bruce Guimaraens.

Learn to live more harmoniously with spontaneous vegetation, to accept its life cycle, and to intervene only as much as necessary to prevent these plants from harming the vines or carpeting the vineyard and raising the risk of fire.

Copper and sulphur are effective, irreplaceable, and complementary fungicides in maintaining vineyard health. Their effectiveness is greatly enhanced by choosing the right moment to intervene.

Taste Terra Prima, the ruby Port produced by Fonseca Guimaraens with grapes from an organic vineyard and fortified with organic brandy. I hope it inspires you to create an organic dry white Port. There is none on the market, a significant gap worth filling.

On the ideal vineyard

Only after learning to respect tradition, people, and the soil can you begin to ask the most difficult question of all: where should a vineyard be planted?

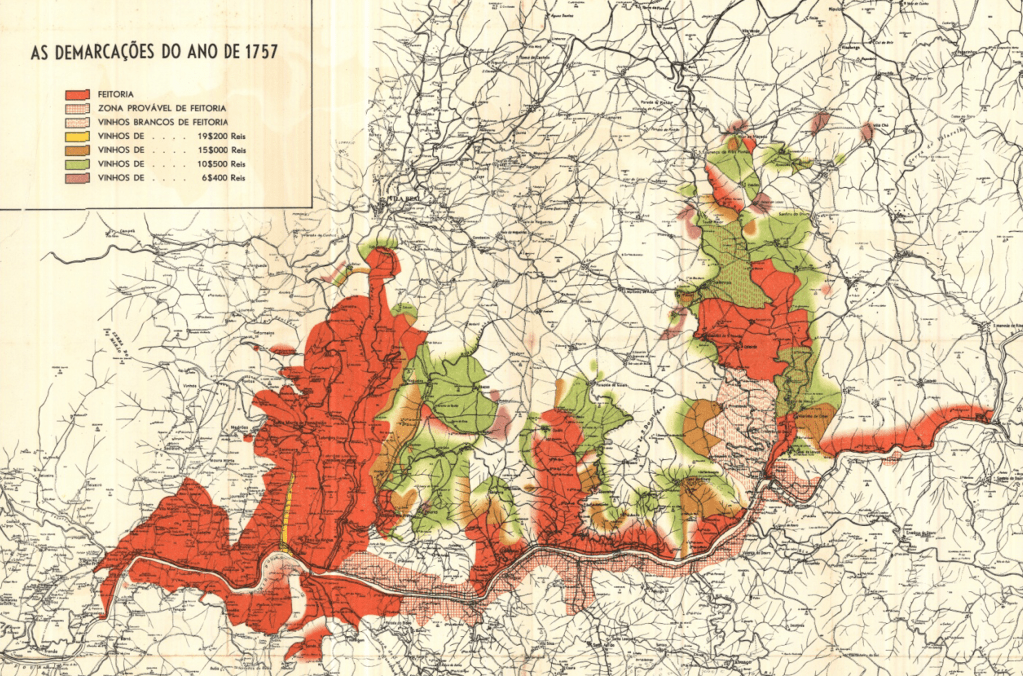

I am firmly convinced that, during the post-phylloxera period through 1965, growers planted the finest vineyards, deliberately choosing sites where vines could naturally thrive. After 1965, and even more after 1980, bulldozers enabled large-scale expansion, and earthen terraces replaced traditional dry-stone walls. Often, these new sites have soils that are either deep or stony and shallow, with poor exposure and a fragile natural water balance. They lack intrinsic viticultural character. Why plant vines in inferior terrain to make room for tractors? A vineyard that does not thrive naturally rarely rewards you with great wine.

Listen to what the landscape is telling you. The old walls indicate where vines once survived without irrigation. The abandoned terraces often mark the limits beyond which quality becomes uncertain. The best lessons are written in stone, not on maps.

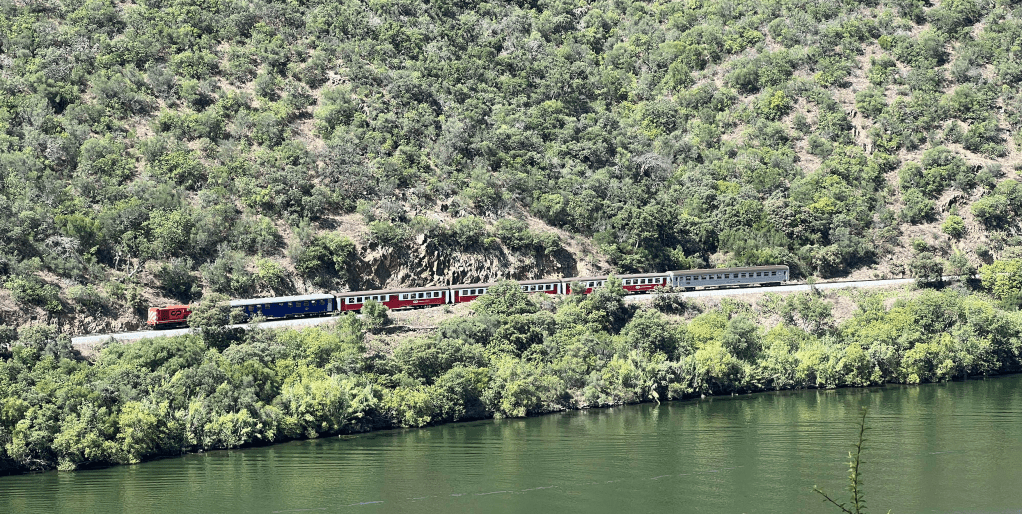

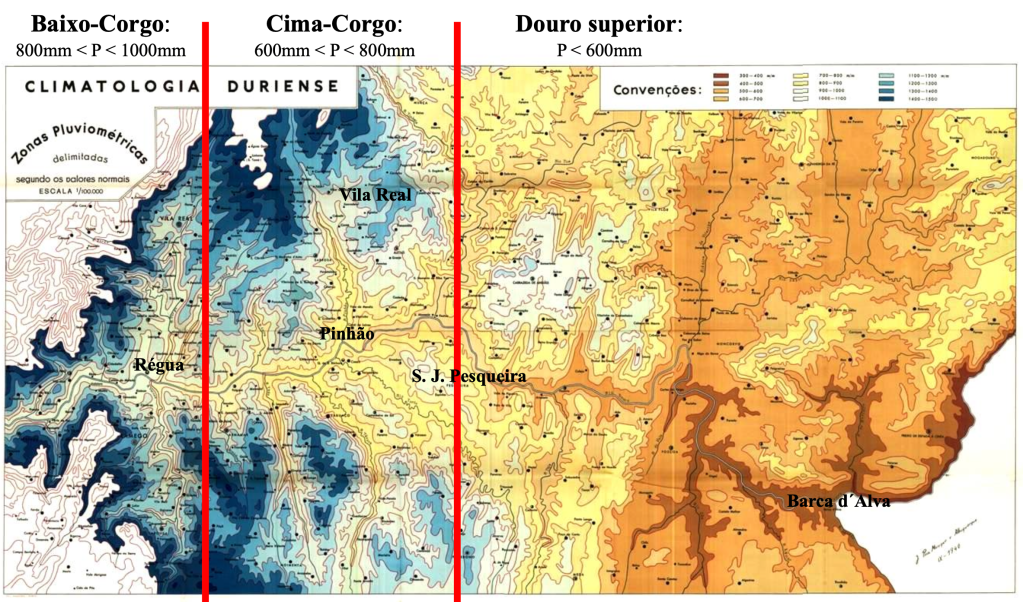

As we travel east from Baixo Corgo to Douro Superior, vineyard density decreases. This fall reflects dwindling rainfall and rising heat. Why defy the logic suggested by the climate by planting vineyards where irrigation becomes necessary?

On the importance of olive trees

Plant olive trees around the vines. Known in the Douro Valley as an olival de bordadura, this natural border frames the vineyard beautifully and yields exceptional olive oil, a valuable additional source of income.

On caring for the vineyard

When you acquire a vineyard, do not rush to renew it. Take time to observe, learn, experiment, and reflect. Pay close attention to the neighboring vineyards. Renewing without understanding what truly needs to change is a serious mistake. A new vineyard should be guided by experience and judgment, never by whim.

On the Douro terraces

Rain causes erosion in hillside vineyards. Careful land design is therefore essential. Vines were once arranged in terraces supported by dry-stone walls. They are now preferably planted on successive narrow stepped platforms, separated by earthen embankments and laid out with laser guidance to ensure, on each level, a longitudinal gradient of about 3 percent, ideal for draining torrential rainfall.

Each terrace is designed to support only a single row of vines (bardo), laid out at a fixed distance from the embankment shoulder to ensure circulation and access for machinery along the slope. At the same time, the terrace width should be reduced as much as possible, increasing vine density without compromising mechanization. This approach uses the land more efficiently and simplifies vineyard work, easing physical labor, which is a priority in mountain viticulture.

On grape varieties

You must study the Douro grape varieties. The choice of what to plant should be shaped by the diversity of soils and microclimates, not guided solely by enological objectives. Planting vines in a new vineyard is like sewing a patchwork quilt, whose meaning and beauty emerge only in the whole. A field blend of judiciously chosen varieties creates the complexity needed for great wines and the resilience to deliver consistency from one vintage to the next.

Let me mention a few of my favorite red varieties. Touriga Francesa is, without question, the conductor of the Douro’s varietal orchestra. It is the most resistant to downy and powdery mildew, a quality that helps explain its prominence in the Douro.

Tinta Cão, which “ripens well, neither shrivels nor rots,” as Francisco Rebelo da Fonseca wrote in the eighteenth century, can be precious in arid years because it survives the heat.

I have a special fondness for Tinta Francisca and Viosinho. They make slender vines, luminous spring hedges, and perfectly ripened grapes, blue-black in the Francisca, golden-yellow in the Viosinho.

Two varieties that can help the Douro face a warming climate are Malvasia Preta and Tinta Aguiar. We need to better understand their properties in the vineyard and cellar.

The Douro is also rich in local white grape varieties. A magic quartet—Malvasia Fina, Viosinho, Rabigato, and Gouveio—forms the backbone of the finest white Ports. On their own or together, they produce outstanding table wines. Beyond these, many other grapes wait to be planted.

On the importance of the blend

The vastness of the region and the diversity of its valleys and hills yield a wide range of grapes. Through blending, producers can create wines with a balance and depth rarely achievable from a single site.

Growers must decide whether a vineyard’s grapes are destined for Port or for table wine (DOC Douro), two different expressions of the same landscape, with any surplus going to simpler, unclassified wines. In any given year, the fruit suits only one style, a vocation that may shift with the weather. As ripening unfolds, the vineyard’s calling becomes clear and is confirmed at harvest. The aim is always to guide each parcel toward its finest possible expression.

On rootstocks

To guard against phylloxera, European vines are grafted onto American rootstocks. The rootstock type is often shared by all vines in a vineyard. One of the earliest and most enduring choices was Rupestris du Lot. To forget it would be to lose history, diversity, and perhaps future resilience.

Today, drought resistance is paramount, so Richter-110 and 1103-Paulsen are common rootstock choices. Both coexist across the valley, but Richter-110 predominates in the Douro Superior and in the Cima Corgo, especially below the mid-slope. 1103-Paulsen tends to perform better in deeper soils with greater spring moisture and is therefore more prevalent in the Baixo Corgo and on the higher slopes of the Cima Corgo.

On planting the vines

I advocate mass selection, propagating vines from many outstanding plants in traditional vineyards, over clonal selection, which reproduces a single “mother vine.” I believe it is the duty of all Douro winegrowers to preserve and multiply our viticultural genetic heritage, especially minor varieties now on the brink of extinction.

On pruning the vines

Cane pruning, known as Guyot, is often the better choice in drier climates or in shallow soils without irrigation. Under such conditions, the individualized, vine-by-vine approach characteristic of this system is justified, and it offers the added advantage of allowing the vines to be continuously renewed.

Yet there are sites and grape varieties that lend themselves better to spur-pruned cordon training, known as Royat: a simple form of pruning, though one that demands no less care and precision in its execution. In the right place, for example, Touriga Nacional benefits greatly from this method, given its somewhat awkward natural growth pattern.

On the harvest

In the Douro, when planted where they belong, vines do not suffer from thirst, only from heat. But before that heat turns harsh, the grapes ripen to perfection for Port. They should never be overripe. Port tolerates only the faintest hint of raisining, and only in limited proportions, in varieties such as Tinta Barroca, Malvasia Fina, and a few others.

In 1992, I learned from Alistair Robertson and Bruce Guimaraens the importance of waiting for the right moment to harvest. Day after day passed without the grapes reaching full maturation. While others chose to pick, Alistair and Bruce held back, convinced that a touch of rain would refine the grapes and bring them to full maturity.

The rain arrived late, at the end of September. It was only 13.5 mm, but Bruce Guimaraens, meticulous about water to the point of counting the drops of morning dew, guaranteed it was enough. His judgement was vindicated: the 1992 Taylor’s Vintage Port would go on to receive a perfect score from Robert Parker.

On Port

Port wine is made without artifice, by people who use simple equipment and have a deep respect for tradition.

Producing a great Port requires a wide variety of grapes, careful choice of harvest dates, and the ability to select grapes by hand in the vineyard.

The proportions of different grapes are adjusted from year to year. Co-fermenting them in the same lagar enhances complexity and balance.

Some final words

It is a privilege to work in the vineyards of the Douro Valley. No other major wine region combines such diversity of longitude, altitude, sun exposure, grape varieties, and soil depth with the production of a fortified wine as delicious, long-lived, and unique as Port.

If you work with patience, with respect for the place, and with attention to what only time can teach, the vineyard will reward you. Not always quickly, but usually honestly.