You might not be familiar with António Magalhães, the chief viticulturist of the famed Taylor-Fladgate port house, but if you enjoy exceptional port wines, you’ve likely experienced the fruits of his labor. António has worked for more than three decades in the rolling terraces of the Douro Valley. Throughout this time, nature has gradually revealed to him some of its winemaking secrets. Patience has been essential in this apprenticeship. It can take many years to grasp the impact of viticulture choices on wine production.

António is known for his thoughtful character and gentle disposition. But beneath this demeanor lies a powerful intellect–he has the rigor of a scientist, the curiosity of a historian, and the eloquence of a poet. He believes in combining scientific methods with traditional wisdom and has a deep reverence for the mysteries of winemaking.

In collaboration with a statistician, António sought to unravel some of these mysteries, analyzing climate data since 1941 to identify weather patterns associated with vintage years, the finest for port wine production. They discovered that these years share three characteristics. First, the average temperature in July is less than 24.5 degrees Celsius. Second, two-thirds of the rain falls during the dormancy period (from November to February) and one-third during the growth period (from March to June). Third, there is less than 20 millimeters of rain in September. A small amount of rain at harvest time helps refine the grapes, says António, but too much rain in September fills the grapes with water and promotes fungal diseases. To António’s delight, they found that exceptional vintage years often deviate from the norm in unique ways, a testament to the magic of port wine.

Another facet of this magic is the art of blending. The Douro’s diverse microclimates provide winemakers with a rich palette to adapt to the annual variations in weather. They skillfully blend diverse varietals from vineyards with different locations, altitudes, and sun exposure. António has a profound understanding of the art of blending grounded on his comprehensive knowledge of the Douro subregions—the rain-soaked Baixo Corgo, the moderately wet Cima Corgo, and the arid Douro Superior.

He has studied how grape varietals were adapted to counter the crisis created by phylloxera, an American insect that decimated European vines in the second half of the 19th century. The blight reached the Douro region in 1862-63 and became a severe problem in 1872. Farmers noticed that Mourisco, a varietal with lackluster enological properties, was the most resistant to phylloxera. For this reason, Mourisco was crossed with Touriga Nacional, considered the finest pre-phylloxera varietal, to create Touriga Francesa. The name, which means French Touriga, was likely chosen to honor the French school of viticulture and its contribution to creating phylloxera-resistant varietals.

António also analyzed the various types of American vine roots brought from places like Texas to the Douro Valley to graft European vines and increase their resilience to phylloxera.

Since 1992, António has worked closely with David Guimaraens, the chief enologist at Taylor-Fladgate. Every year, António and David write several letters to the farmers who produce grapes for Taylor-Fladgate, offering insights into the vines’ current conditions and the most effective viticulture practices to respond to them. This educational effort is vital to the quality of the Taylor-Fladgate ports.

Concerned with the impact of heavy rainfall on soil erosion, António and David developed a new model for the terraces where the vines are planted. They had an epiphany while visiting the Benziger family, a biodynamic wine producer in California. It started to rain torrentially, and as they ran for shelter, they noticed that the rain was running with them. They realized that this kind of drainage, created by a three percent gradient, is what the Douro Valley needs.

António and David asked earthmoving companies to find a bulldozer narrow enough to fit in the terraces and capable of creating a three percent inclination. One of the companies found a second-hand machine used in rice plantations in the south of Portugal. The company’s manager called to say that the machine had an unusual device. “Bring it along,” said António. It turned out that the device was a laser that greatly simplified the task of creating a three percent slope. They later learned that the Benziger farmland had been graded by Chinese workers, who were likely to be familiar with the three percent inclination used in rice cultivation.

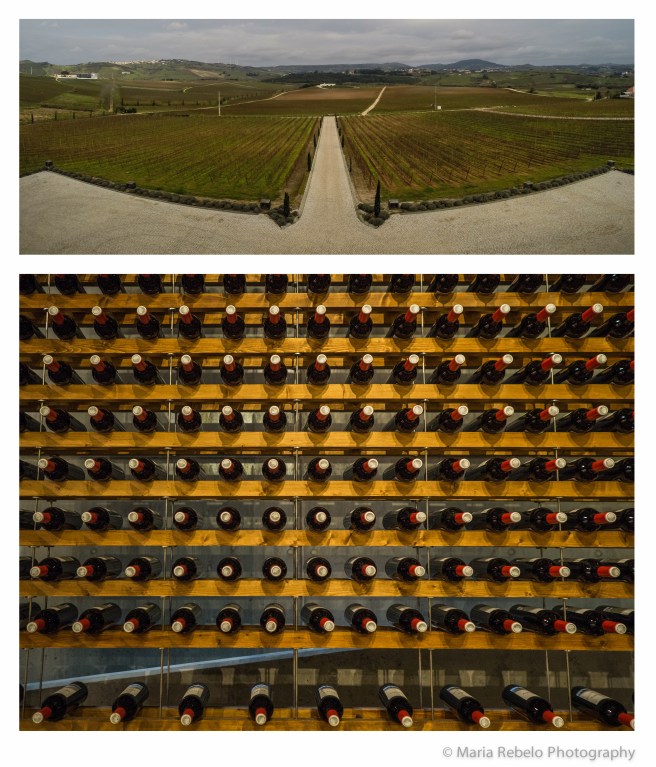

The Taylor-Fladgate farms stand out for their beauty because António is a sculptor of landscapes. He knows that cultivating a vineyard, planting a tree, or building a stone wall alters the scenery, and like an artist, he selects colors that harmonize, proportions that feel human, rhythms that please the eye.

António is passionate about researching the history of the Douro region. He often visits Torre do Tombo, a vast national archive with documents spanning nine centuries of Portuguese history. The writings of Álvaro Moreira da Fonseca (the creator of the vine quality scoring system still in use), the Baron of Fladgate, John Croft, José Costa Lima, A. Guerra Tenreiro, and many other Douro luminaries are his constant companions.

His extensive knowledge of history gives him a unique appreciation for the sacrifices made by generations of workers who have toiled in the Douro region. This understanding is evident in how António interacts with the people he manages. His sincere appreciation for their efforts earns him the loyalty and trust of his collaborators.

Today, António Magalhães retires as Taylor-Fladgate’s chief viticulturist. This milestone marks the beginning of a new chapter. We hope that António can now find the time to write a treatise on viticulture so that, as the climate continues to change, his erudition can illuminate the future of the Douro Valley.