All southern European countries have their own fisherman’s stew. In Portugal, this classic dish is called caldeirada (pronounced “qaldeirahda”). It’s an appropriate name, since caldeira means caldron, a pot used in alchemy. When you combine fish, vegetables, and white wine, the result is indeed magical.

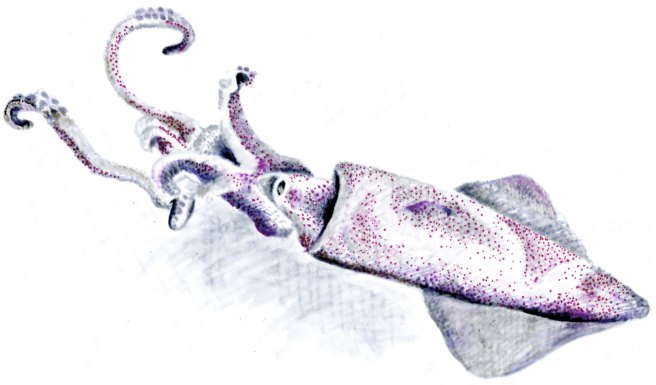

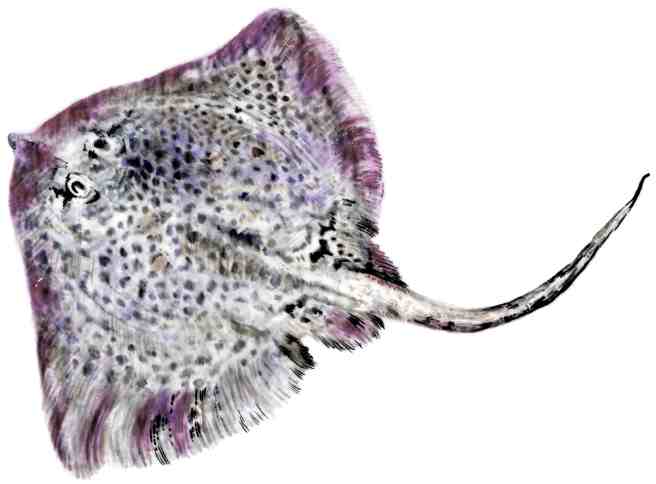

You can use different fish varieties, but the star of the caldeirada is the skate. Its delicious white flesh combines perfectly with the rich stock.

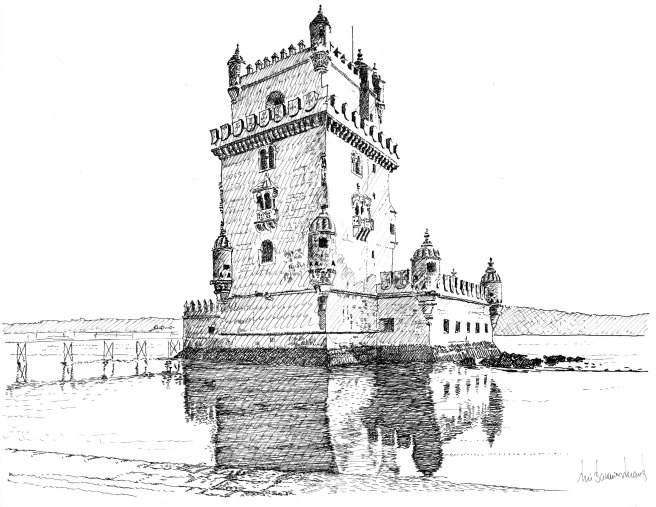

The best places to eat caldeirada are near the ocean because this dish requires the freshest fish. According to Marcel Pagnol, the French writer born in Marseille, the secret of the fisherman’s stew is to put the fish in the pot while their tails are still moving. If you’re near the Portuguese coast, don’t miss a chance to eat a memorable caldeirada.