In our sixth lecture with viticulturist António Magalhães, we turn to a group of unloved grape varieties that are often dismissed, yet fully capable of producing great wines when planted and farmed wisely

Tinta Roriz

For over thirty years, António met each August with David Guimaraens, head winemaker at Taylor Fladgate. Together, they assessed the evolution of the two grapes most critical to the Vintage Ports of Fonseca Guimarens: Touriga Francesa and Tinta Roriz. António grew to admire Tinta Roriz’s distinctive qualities and came to reject its poor reputation. Tinta Roriz may well be the Douro’s most misunderstood grape.

Tempranillo arrived in the Douro from Spain and was initially called Aragonez, the name it still bears in other Portuguese regions. By the late nineteenth century, it became known as Tinta Roriz, reflecting the distinct identity it had acquired in the Douro.

It plays a crucial agronomic role: its disease sensitivity makes it a sentinel vine, offering early warning of downy and powdery mildew, the green leafhopper, and maromba (a boron deficiency common in the Douro).

Tinta Roriz is one of the grapes farmers call paga dívidas (“debt payer”) because it can produce large, heavy bunches, particularly in years of abundant rain. Many enologists, however, associate the grape with large, watery berries that yield thin, forgettable wines. And yet Tinta Roriz plays a starring role in some of the Douro’s greatest wines. Why? There are three reasons.

First, lineage. The finest examples of Tinta Roriz come from old vines, whose cuttings far outperform modern clones.

Second, site. Tinta Roriz must be planted in poor soils and in sites with good sun exposure and sufficient airflow to protect it against mildew and oidium.

Third, rootstock choice. The adoption of highly productive rootstocks, like the 99 Richter, rather than those better suited to the Douro terroir, notably the Rupestris du Lot, boosted yields at the expense of quality.

So why has Tinta Roriz so often disappointed? Many of today’s vineyards date from the late 1980s and early 1990s, when mechanization reshaped the Douro. Wide terraces were carved into the hillsides, and vines were planted at low density to accommodate tractors. To offset that lower density, growers favored productive varieties like Tinta Roriz. They chose high-yielding clones, fertile soils, and vigorous rootstocks. In some cases, they also replaced dry farming with irrigation, sacrificing deep root systems and the hydric stress that concentrates flavor. It is hardly surprising that the grape’s reputation suffered.

And yet, in the right hands, Tinta Roriz shines. The iconic Pintas, produced by Sandra Tavares da Silva and Jorge Serôdio Borges and made from more than forty grape varieties, contains 10–15 percent Tinta Roriz.

Tinta Barroca

This grape plays a secondary but essential role in Port blends. It is present in virtually all vineyards planted before the mid-1980s. Later plantings, no longer based on traditional field blends, sometimes exclude it—to their loss.

Because it is usually part of a blend, Tinta Barroca dwells in relative obscurity. Yet it has always had its champions. José António Rosas, the renowned winemaker of Ramos Pinto, was a great admirer.

Bruce Guimaraens, the larger-than-life British winemaker of Fonseca Guimaraens, also held it in special esteem. Struggling with the two Rs, he called it “Baroca.” His son David shares his father’s appreciation for the grape but pronounces “Barroca” like a proper Portuguese.

It is an early-ripening variety, and the first impression when tasting the berries is its candy-like sweetness. Like Malvasia Fina, the berries are particularly delicious when they are about to turn into raisins. At that moment, they reach the upper limit of ripeness acceptable for Port.

Like Touriga Francesa, Tinta Barroca is an offspring of Mourisco Tinto and Touriga Nacional. António suspects that it may be the modern name for the pre-phylloxera variety Boca de Mina (“mouth of the mine”), a name that hints at its need for freshness. The Baron of Forrester considered Boca de Mina “the most delicious,” and João Cunha Seixas, a prominent viticulturist, praised it in his “Guide for the Douro Farmer,” published in 1895.

Tinta Barroca is highly sensitive to heat. This attribute was largely forgotten in the vineyards planted in the late 1980s and 1990s, when it was often placed in sites with excessive sun exposure. As a result, the rachis cooks and the berries shrivel and mummify. You can almost hear the vines pleading, “Take me out of here.”

Barroca is often accused of being ill-suited to a warmer climate. Yet in the right site, the vine can thrive and produce beautiful wines. One striking example is at Quinta do Cruzeiro in Vale de Mendiz, where Tinta Barroca dominates a vineyard called Patamares do Norte (northern terraces), a name that signals the vineyard’s favorable north-facing exposure, which suits the grape so well.

Tinta Barroca and Tinto Cão are complementary varieties. Every year, António and David Guimaraens faced the difficult yet enticing challenge of finding their ideal proportions for Port.

Tinto Cão

Tinto Cão is often dismissed for lacking deep color, opulence, and high alcohol. Yet there is a long tradition of appreciation for this variety. In his Agricultural Memoirs of 1790, Francisco Rebello da Fonseca praised it, noting that “amadura bem, não seca nem apodrece”—it ripens well, without shriveling or rotting. He also mentions wine made from Tinto Cão by Manuel Vaz de Carvalho that was “considered superior to all his others and to those of the surrounding area.”

This grape has long been a quiet ally in difficult years. For António and David Guimaraens, Tinto Cão is a joker in the deck, saving great Ports in dry vintages such as 2009, 2011, and 2017.

It produces small berries with thick skins, yielding wines with natural acidity, elegant tannins, and remarkable aging potential. It may disappoint in cool years, but it shines in warm ones.

Tinto Cão thrives in vines with a south-westerly exposure, at altitudes below 300-350 metres. Above all, it demands deep soils to allow the grapes to ripen under a scorching sun.

If Francisco Rebello da Fonseca were alive today, he would relish seeing Tinto Cão escape the confines of Port wine. An increasing number of Douro estates, including La Rosa and Noval, are making delightful table wines exclusively from Tinto Cão. Luisa Borges, the winemaker and owner of the Vieira de Sousa estate, is especially fond of wines made from this variety.

In Vintage Ports from Taylor Fladgate and Fonseca Guimaraens, Tinto Cão remains a secondary but essential variety.

António keeps a mental list of grapes best equipped to help the Douro thrive in a warmer climate. At the top of that list is Tinto Cão.

Tinta Amarela

Tinta Amarela is a striking vine year-round and among the last to shed its leaves in autumn. Yet it is finicky: its dense bunches are vulnerable to heat and rain, which can trigger sour rot, as damaged berries are colonized by yeasts and acetic bacteria, leading to vinegar-like spoilage.

Site selection is everything. An east-facing exposure is generally ideal. Below the mid-slope line, row orientation becomes decisive, as it governs how much sun the clusters receive: rows facing east protect grapes from harsh heat, while those facing west leave them overexposed.

The vine can survive hot summers in the arid Douro Superior, but the grapes vanish. Farmers say, “the vines drank the grapes.”

Tinta Amarela appears in modest quantities in many old vineyards, particularly in Baixo Corgo, and is therefore most often found in blends. Single-varietal wines are rare.

It plays a major role in Quinta do Crasto’s celebrated Maria Teresa. Drawn from a field blend of centenarian vines planted around 1906 on low-altitude, east-facing terraces along the Douro River, the wine owes its distinctive character to afternoon shade that tempers the heat.

Tinta da Barca

Tinta da Barca is, like Touriga Francesa, a cross between Mourisco Tinto and Touriga Nacional. Yet while Touriga Francesa is widely planted and well known, Tinta da Barca remains largely obscure.

David Guimaraens is a devoted advocate of the grape, which plays a quiet but crucial role in the great Vintage Ports of Quinta de Vargellas. The fruit comes from the Pulverinho vineyard, planted in 1927 with both Touriga Francesa and Tinta da Barca.

António believes the best introduction to Tinta da Barca is a wonderful monovarietal table wine made by Ramos Pinto in 2016, a challenging year marked by heat and an unusual outbreak of downy mildew, which nonetheless yielded both classic Vintage Ports and outstanding table wines. It has been one of his favorites ever since.

Malvasia Fina

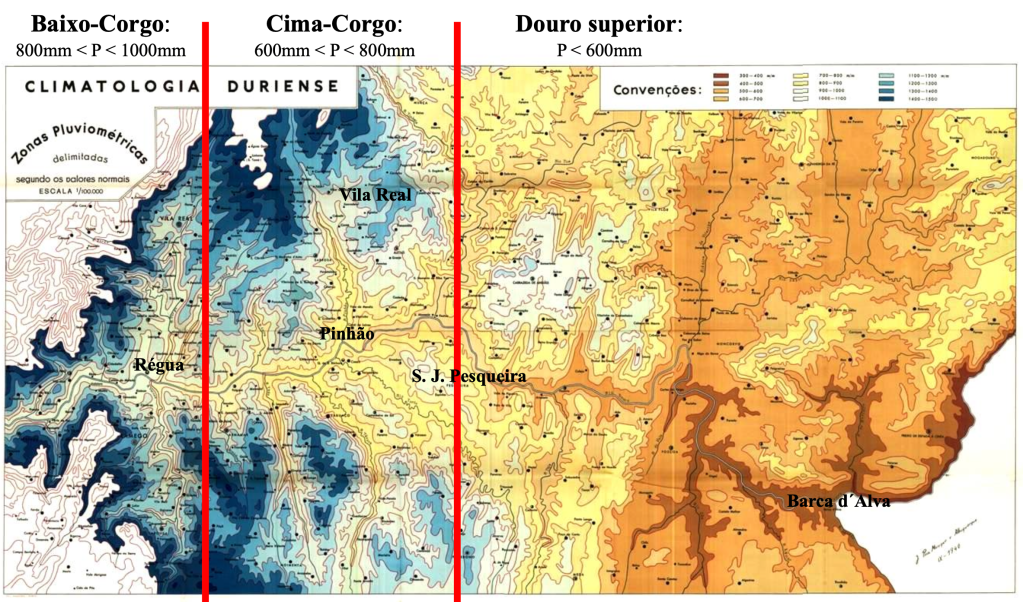

António knows, like the palm of his hand, remarkable Malvasia Fina vineyards across all three Douro subregions: Baixo Corgo, Cima Corgo, and Douro Superior. When planting this grape, one factor matters above all others: altitude. For Port wines, the ideal locations lie above 350–400 meters; for table wines, between 500 and 600 meters.

Malvasia Fina plays an indispensable role in several outstanding white Ports, including Fonseca Guimaraens’ Siroco and Taylor Fladgate’s Chip Dry, as well as in Adriano Ramos Pinto Finest White Reserve, a delightful sweet white Port.

In terms of table wines, António likes the white Reserva from Quinta do Cume in Provesende—a wonderful blend led by Malvasia Fina, with Rabigato, Viosinho, and Gouveio in supporting roles.

For those eager to discover how expressive the grape can be, António recommends tasting the Quinta do Bucheiro Malvasia Fina Reserva made by Dias Teixeira, an octogenarian and former enologist at Borges Port Wine, who knows Malvasia Fina’s secrets and charms.

After our lecture, António had lunch at a seafood restaurant and let the sommelier select the wine. The choice was excellent: a Viosinho from D. Graça. When António asked which Malvasia Fina wines the sommelier would recommend, the reply was blunt: “I don’t like that grape variety.” Malvasia remains, clearly, misunderstood.

Each grape in its place

António teaches a lesson that should not be forgotten: grape varieties cannot simply be uprooted from one place and expected to thrive elsewhere. Each has a place where it speaks clearly. Many of the Douro’s unloved grapes were simply misplaced. Put them back where they belong, farm them with respect, and they repay the favor with wines of character, balance, and beauty.