António Magalhães, former chief viticulturist of Taylor Fladgate, is revered throughout the Douro for his deep knowledge of its vineyards and terroir. He graciously agreed to give us a series of master classes about the Douro, and what follows are notes from the first of these sessions—an insider’s look at one of the world’s most extraordinary wine regions.

About António

António was born in Régua, in the heart of the Douro. Both of his parents came from families who cared for their own vineyards. He often spent time at his maternal grandfather’s estate, where his love for the Douro was first nurtured. Although he never inherited land, his studies were guided by a single calling: to work among the vines of his native valley.

A Land of Mountains and Microclimates

The Douro is immense — 250,000 hectares of rugged mountains, of which only 44,000 are occupied by vineyards. It is the largest mountain viticulture region in the world, and the only one with a Mediterranean climate crossed by a navigable river that flows into the Atlantic Ocean.

The basin of the Douro, the largest in the Iberian Peninsula, is shared by Portugal and Spain. Its main river and tributaries flow through a tapestry of vineyards across wine regions: Ribera del Duero, Rueda, Cigales, Toro, and Arribes, in Spain, Douro and Távora-Varosa in Portugal. You could say that the Douro is a river of wine.

The Douro’s rise as a great wine region began in 1703, when Portugal signed the Methuen Treaty with England, opening trade between the two nations. Douro’s Port wine became popular in England, and demand soared. Vineyards spread, and some producers began to cut corners—darkening their wines with elderberry juice and sweetening them with sugar. Port’s reputation faltered, and trust among English importers began to erode.

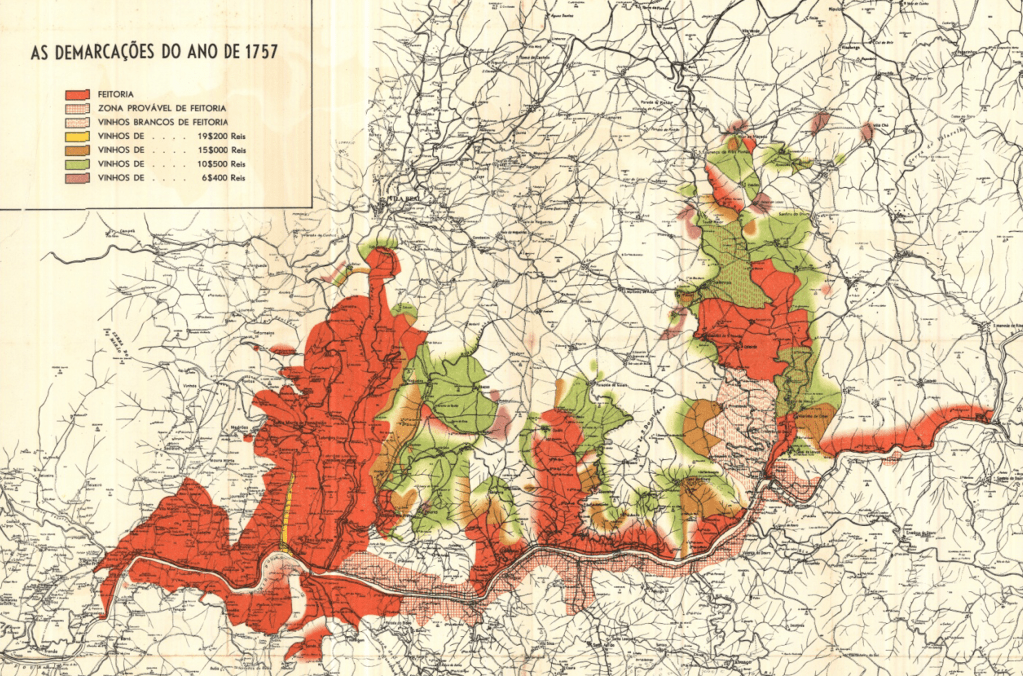

To restore order, avoid the use of fertile land for viticulture, and protect Port’s reputation, the Marquis of Pombal created the world’s first demarcated wine region in 1756. The Companhia Geral da Agricultura das Vinhas do Alto Douro, a public company, marked its boundaries with granite pillars known as marcos pombalinos and classified its vineyards. The finest plots produced the prized vinhos de feitoria, destined for the great British trading houses (feitorias) in Porto. Wines of intermediate quality, the vinhos de embarque, were partly exported, while the more modest vinhos de ramo were reserved for local consumption. With this demarcation, a singular landscape was born, shaped by nature’s hand and human will.

It was fortuitous that there was open land in Gaia, near Porto, on the southern bank at the mouth of the Douro. There, the north-facing slopes and the cooler, more humid weather provided ideal conditions for storing and aging wine. With its quality safeguarded and easy access to an Atlantic port from which ships could carry it abroad, Port wine flourished, becoming prized around the world.

The climate and regions of the Douro

On what António calls the “Olympic podium” of terroir, climate wins gold, soil takes silver, and grape varieties bronze. Today, we focus on climate.

Vines don’t need irrigation, but they do require at least 500 mm of rainfall per year. In the Douro, however, the irregular rainfall and rapid runoff down the steep slopes increase that need to about 600–700 mm. The timing of that rain is crucial. It rains about as much in Pinhão, at the center of the Douro, as in Paris—around 640 mm annually. However, in the capital of France, rain falls throughout the year, whereas in the Douro, the rain is in tune with the vines’ vegetative cycle: it falls mainly in autumn and winter, when the vines are dormant. Planted in the right places, Douro vineyards never suffer from thirst, only from heat.

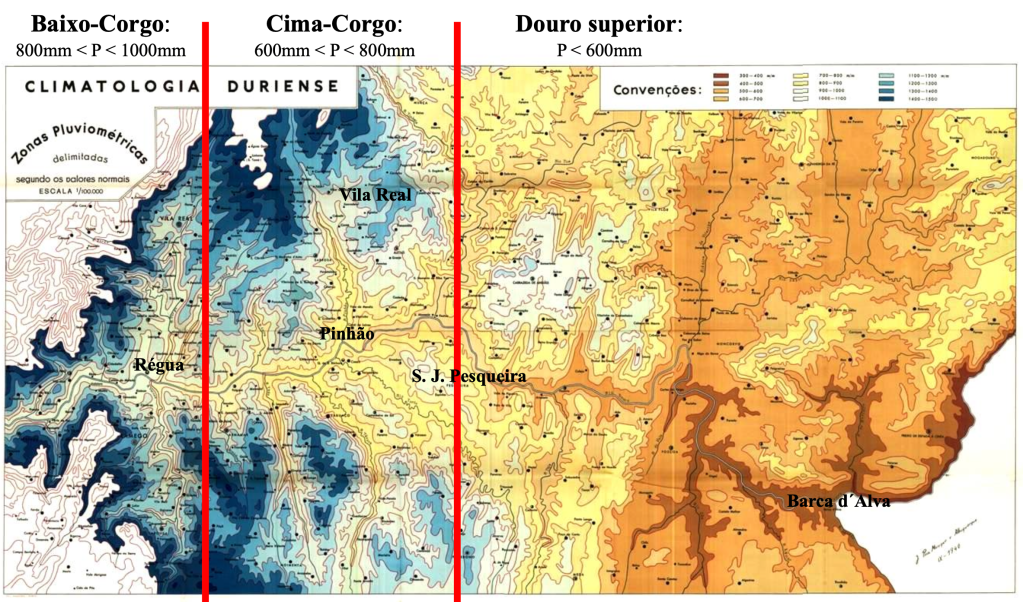

The distribution of rainfall divides the Douro into three distinct subregions. Baixo Corgo is lush and green, blessed with 800 to 1,000 mm of rain each year. Cima Corgo, home to the great Port houses, is drier, with 600 and 800 mm. Farther east lies Douro Superior — sun-scorched, rugged, and remote, where rainfall often falls below 600 mm.

Vineyards are abundant in Baixo Corgo and sparse in Douro Superior, where cultivation is possible only in small islands with favorable microclimates. In recent decades, irrigated vines have appeared in Douro Superior, yet they rarely produce grapes suitable for making Port.

The scholar Alfredo Guerra Tenreiro wrote that “there is a uniqueness in the Douro climate that one can feel in the uniqueness of Port wine.” In the 1940s and 1950s, he mapped the aridity of the Douro using a simple measure: average temperature multiplied by 100, divided by rainfall. As one moves west or climbs the surrounding hills, aridity decreases because the temperature falls and rainfall increases.

As we ascend the hills that flank the Douro and its tributaries, the temperature drops roughly 0.65°C per 100 meters. With peaks rising to 600 or 700 meters, temperatures can be as much as 3.6°C cooler than in vineyards planted near the river, at 100 meters of altitude.

Orientation also matters. South-facing slopes are, on average, two degrees warmer than north-facing ones during the summer — a subtle difference with dramatic effects. It explains why the Douro can yield everything from festive sparkling wines, such as Celso Pereira’s Vértice, to bright whites, velvety reds, and opulent Ports.

Álvaro Moreira da Fonseca used location, altitude, and orientation to craft his brilliant classification of the region’s vineyards, grading them from A to F. This system still underpins the benefício rules that determine how much of a vineyard’s production can be used for Port wine. His maps, drawn in 1944 and 1945, are masterpieces. Fonseca set 500 meters as the upper limit for Port production, deducting points for vineyards planted above that line.

Looking at Fonseca’s maps, we see a “blessed valley” — Vale de Mendiz, where the Pinhão River meets the Douro. There, rainfall from the Baixo Corgo meets the warmth of the Cima Corgo, producing wines of exceptional balance. It is no coincidence that iconic estates like Quinta do Noval and Wine & Soul call Vale de Mendiz home.

Traveling Through the Douro

António recommends visiting the Douro between mid-May and mid-November, staying for several days to ensure you catch a sunny spell. Gray skies hide some of the valley’s splendor.

He suggests two journeys for those eager to understand the Douro.

First, drive along the A24 highway from Vila Real to Régua, crossing the Marão mountain — an invisible wall separating cool Atlantic air from the dry Mediterranean hinterland. You’ll cross the Baixo Corgo moving perpendicular to the course of the Douro River. The landscape is breathtaking, and along the way you can feel the shifts in temperature and altitude that shape the character of Douro wines.

Begin in Vila Real at 450 meters of altitude, and as you descend toward Régua, at 100 meters, feel the temperature rise and watch the hills unfold into a sea of vines. Olive trees stand like sentinels at the edges of vineyards. Climb toward Lamego, at 540 meters, and feel the air cool once more. The whitewashed houses, stone wine lodges, and hillside villages lend a human touch to the landscape, making the journey unforgettable.

In Régua, stop at Aneto, a small, family-run restaurant where hospitality flows as generously as the wine produced in their own estate. In Lamego, stop at Pastelaria Velha da Sé for a bola de carne (savory meat-filled bread), visit the cathedral, the Escadório de Nossa Senhora dos Remédios, a Baroque stairway, and admire the Ribeiro da Conceição theater, a miniature La Scala.

The second journey is by train, linking three UNESCO World Heritage sites: Porto, the Douro, and the Côa Museum, which preserves paleolithic art.

The hills were carved to lay the train tracks, turning the voyage into a geology lesson on Douro’s mother rock, the schist. Its cleavage is almost vertical, allowing the vine roots to penetrate deeply into the cracks in search of precious water.

As the train leaves Régua, schist terraces rise and curve around the river. Disembark at Pinhão and linger a few days visiting nearby wine estates. Before you go, admire the station’s twenty-four azulejo panels, made in 1937 by the Aleluia Factory in Aveiro. They depict the Douro landscape and trace the making of Port—from the harvest of sun-ripened grapes to the voyage of slender rabelo boats, which carry barrels to the cellars of Vila Nova de Gaia.

Continue upriver through the Cima Corgo, the heartland of Port. In bygone days, train-station restaurants were famed for their quality. Calça Curta, at Tua Station, keeps this tradition alive. Farther along, stop at Ferradosa Station to dine at Toca da Raposa, celebrated for its regional cooking.

As the train enters the Douro Superior, the air turns drier, the heat more intense, the hills steeper. At Cachão da Valeira, the landscape shifts to granite. Today, the river glides wide and serene, but it once raged against a massive granite barrier that made navigation perilous. Here, in 1861, tragedy struck: a boat capsized carrying two iconic figures—Dona Antónia Ferreira, owner of vast wine estates, and the Baron of Forrester, an English merchant and mapmaker who devoted his life to the region. According to legend, Dona Antónia survived, buoyed by her billowing skirts, while the Baron drowned, dragged down by the gold coins in his pockets.

In summer, cicadas sing for travelers along the stretch between the Valeira gorge and Pocinho. As you near Pocinho, the heat intensifies—writer Francisco José Viegas once quipped that “hell’s heat comes from Pocinho.” Stop at Taberna da Julinha, a local restaurant that, in the summer, serves the valley’s celebrated tomatoes, bursting with flavor and sweetness.

The Côa Museum lies about 10 kilometers from the train station. There, you can contemplate the largest and oldest ensemble of open-air Paleolithic engravings in Europe. Horses, deer, and goats emerge from the stone, their lines layered in a dance of timeless motion. Dine on the museum’s terrace, overlooking the river laid bare in all its austere beauty—terraces and cliffs carved by nature and human will.

The Future of the Douro

The Douro was forged in hardship. Its people labored to carve terraces from unforgiving slopes; its vines learned to endure searing summers and biting winter frosts. Yet this endurance may be the valley’s greatest gift. It has prepared the Douro to face the trials of a changing world.