The Romans called it Felicitas Julia, a city so blessed it deserved Julius Caesar’s protection. Those blessings endure: a mild climate, a deep river that flows serenely to the sea, a natural harbor that shelters ships from Atlantic storms, and hills that reach for the sky.

In 1620, Friar Nicolau de Oliveira wrote that Lisbon, like Rome, has seven hills. In truth, there are only three major elevations: the castle hill, Graça, and Bairro Alto. But in spirit, he was right: the streets rise and fall so much that, in the early 20th century, trams and elevators were built to help residents get around.

First Day

Begin your visit at St. George’s Castle. In the twelfth century, most of Lisbon lay within its walls. Below lies Alfama, whose Arabic name survived the city’s conquest by Portugal’s first king, Dom Afonso Henriques, in 1147. According to legend, a knight called Martim Moniz sacrificed his life, wedging his body in the castle gate so his fellow soldiers could break through. A square at the foot of the hill bears his name.

By the eighteenth century, Alfama was a poor neighborhood. The wealthy had relocated to Baixa, Bairro Alto, and Chiado. The 1755 earthquake devastated much of Lisbon but spared Alfama, a survival some interpreted as divine justice.

It is easy to get lost in Alfama’s winding streets lined with cobblestones, tile facades, and marble thresholds. A simple rule will help you find your way: uphill leads to the castle, downhill to the city center.

From the castle walls, the Tagus River dominates the horizon. Below lies Terreiro do Paço, the courtyard of the royal palace destroyed by the earthquake. Squint and you might imagine Baroque carriages arriving with courtiers seeking the king’s favor.

For a leisurely lunch, walk toward the Pantheon, a monumental church whose construction spanned more than three centuries. Nearby, Solo, inside the Santa Clara 1738 hotel, offers refined Portuguese cuisine made with the finest ingredients and served in an elegant setting.

After lunch, continue to Terreiro do Paço. At the river’s edge stands Cais das Colunas, the dock marked by two marble pillars where visitors once arrived by ship. Before air travel, this was Lisbon’s grand entrance. In the center of the square, the equestrian statue of King Dom José I greets you.

Walk toward the triumphal arch at the entrance of Augusta Street, named for one of the king’s daughters. You can take an elevator to the top for superb views. To the west stretches the Tagus River; to the east lies the orderly grid of the Baixa district, built after the earthquake under the direction of the king’s prime minister, the Marquis of Pombal.

The streets were organized by trade. In Rua do Ouro and Rua da Prata (Gold and Silver Streets), jewelers worked the precious metals arriving from Brazil. Merchants on Rua dos Fanqueiros sold woolen cloth, while Rua dos Correeiros specialized in leather equipment for horses and carriages.

From there, walk to Rossio. On the way, stop at Largo de São Domingos to savor a glass of ginjinha, the sweet cherry liqueur beloved by poet Fernando Pessoa.

Next, climb to Chiado for a pastel de nata at Manteigaria, where the crust is perfectly crisp and the custard delicately perfumed with lemon. Eat only one. Then cross to the Hotel do Bairro Alto terrace for a second. Try not to let the sweeping view cloud your judgment: which pastry wins your favor? The terrace is a wonderful place to rest before dinner. We include a list of restaurant suggestions below.

After dark, nothing expresses Lisbon’s soul like fado. Dressed in black, singers are accompanied by classical and Portuguese guitars, the latter a 12-string instrument with a distinctive mournful sound. Out of respect for the music, the audience is asked to remain silent. The singers’ voices hover between notes, producing pitches that a piano cannot play. They slow or quicken the tempo, confident that the musicians will follow. We are especially fond of the young fadista Beatriz Felício. If she is performing, don’t miss her.

Second day

Start the day at the Time Out market. Many come for a quick meal, but you’re here to visit the adjacent farmers’ market. Browse the seasonal fruits and vegetables on display, then stop by the fish stall, which showcases some of the world’s freshest fish.

If you need refreshment, Bar da Odete offers a wonderful range of wines by the glass, curated by enologist Frederico Vilar Gomes. You can buy some of these wines at Garrafeira Nacional, a shop inside the market.

Continue toward Belém to visit the Belém Tower, an ornate fortress built to defend Lisbon from pirates, yet making the city even more alluring. Before the 1755 earthquake, the tower stood in the middle of the river rather than near the shore.

To the south stands the Monument to the Discoveries, a procession of stone figures led by Prince Henry the Navigator. Beginning in the 1420s, Portuguese sailors departed from Restelo into the unknown in ships called caravels, which, for the first time, could tack to sail against the wind.

In his epic poem Os Lusíadas, Luís Vaz de Camões imagines an old man on the shore warning that the quest for glory would bring suffering rather than triumph. In material terms, the discoveries were an extraordinary success. Vasco da Gama reached India, opening a sea route for the spice trade. Cabral reached Brazil, and ships soon returned to Lisbon laden first with brazilwood and, later, with gold. Yet these riches came at a terrible human cost. Many sailors perished in shipwrecks or from diseases, especially scurvy, caused by months at sea without fresh provisions, living on little more than hard biscuit.

Just to the east rises the magnificent Jerónimos Monastery, built with the wealth of the maritime empire. Its Manueline architecture blends late Gothic style with nautical motifs. Inside are the tombs of kings and queens, as well as Vasco da Gama and Luís Vaz de Camões.

To the north is the Cultural Center of Belém, a modern art complex built from stone from the same quarry as the monastery. Its concerts and exhibitions are worth checking out.

If you crave grilled fish, the modest O Último Porto, open only for lunch and patronized mostly by locals, serves fresh fish grilled to perfection. Robalo is always a great choice, and the mullets are divine.

Skip dessert. You must return to Belém for the city’s most famous custard, the Pastel de Belém. The bakery has produced them since 1837, using a secret recipe shared by monks after the dissolution of the religious orders in 1834. Enjoy one warm pastry dusted with cinnamon, a fragrant echo of the spice trade that enriched Portugal. Now that you have tasted the city’s most celebrated pasteis de nata, which is your favorite?

End the day at MAAT, the Museum of Art, Architecture and Technology. It offers interesting exhibitions and a roof that is one of the finest places to watch the sunset in Lisbon. As the sun sinks into the Atlantic, Lisbon’s hills glow amber, the color of the gold that once made it rich.

Here are some practical suggestions

Where to stay

Our favorite place to stay in Lisbon is Santa Clara 1728, a small hotel that exudes tranquility and elegance. It is part of Silent Living, a unique collection of hotels designed to help guests reconnect with place and nature.

The Pestana Palace, built around an early-20th-century palace, is another favorite. Set away from the center and surrounded by gardens, it offers a peaceful respite from the city’s bustle.

The Ritz Four Seasons is a mid-century modern landmark that provides classic old-world luxury.

Hotel do Bairro Alto, in the heart of Chiado, combines a central location with excellent service.

Where to eat

Not long ago, one could walk into almost any restaurant and enjoy an honest, modestly priced meal of local food and wine. Today, many restaurants cater primarily to tourists. To taste authentic cuisine, you need guidance, but rest assured, we’re here to provide it.

Lisbon’s fine-dining scene is vibrant. Belcanto, led by José Avillez, has elevated Portuguese cuisine while staying true to its roots. His recent book on Portuguese cuisine makes a wonderful gift for a gourmet friend. Marlene, by chef Marlene Vieira, reinterprets tradition with imagination and finesse. Loco, led by chef Alexandre Silva, offers exuberantly creative dishes made with local ingredients.

Beyond the Michelin constellation, many excellent restaurants await discovery. We mentioned two of our favorites in the main text. Solo offers a lunch menu where each dish is crafted from pristine organic ingredients sourced from Casa no Tempo. Último Porto is a rustic restaurant known for perfectly grilled fish.

Zun Zum, Marlene Vieira’s bistro, showcases superb Portuguese ingredients prepared with inventiveness. Try their signature dish: “filhoses de berbigão,” large cockles served on star-shaped fried dough filled with a cream made from cockle broth, coriander, and lemon.

For seafood, Cervejaria Ramiro remains our top choice. It is noisy and crowded, but it is worth it. Reservations are not accepted, so arrive early. Do not miss the clams à Bulhão Pato, a classic of Portuguese cuisine.

Tasca da Esquina, by Vítor Sobral, consistently serves excellent interpretations of traditional dishes.

Canalha offers impeccable seasonal ingredients, prepared with precision. This acclaimed bistro is led by chef João Rodrigues, who left his Michelin stars behind to cook simple, deeply satisfying food.

Casa Tradição offers inventive takes on classic recipes by Samuel Mota, a chef who trained at Belcanto.

Our favorite vegetarian restaurant is Touta, led by Lebanese chef Cynthia Bitar.

Other favorites include Belmiro (excellent empadas and rice dishes), Salsa e Coentros, and Magano.

For wine lovers, we recommend a visit to Quinta de Chocapalha, a superb producer near Lisbon.

Museums

The Calouste Gulbenkian Museum has one of the world’s finest private art collections, reflecting the founder’s motto: “only the best.” A visit is a journey spanning 5,000 years of human creativity. Among the collection’s highlights is Almada Negreiros’ portrait of the poet Fernando Pessoa.

Two major museums are currently closed for renovations. The Museu Nacional de Arte Antiga preserves Portugal’s most important collection of paintings, sculptures, and decorative arts. Housed in a former convent, Museu Nacional do Azulejo offers a collection of five centuries of Portuguese tile art, including a breathtaking panoramic panel of the city before the 1755 earthquake.

Shopping

We love Vista Alegre, a company that has produced beautiful porcelain since 1824. Its stores are spread throughout the city, with the most iconic located in Chiado. Nearby is Cutipol, a producer of elegant cutlery.

A Vida Portuguesa offers a carefully curated selection of artisanal products made with exceptional craftsmanship.

Reverso is a jewelry gallery featuring whimsical, elegant modern pieces.

Activities for kids

A visit to Lisbon’s outstanding Oceanarium is a perfect activity not only for kids but for anyone interested in the mysteries of the ocean and the protection of marine ecosystems.

Cruising the Tagus River aboard Santa Fé, a beautifully restored vintage boat, is one of the best ways to see the city.

Jezzus is a great place for pizza, a meal that kids are likely to enjoy.

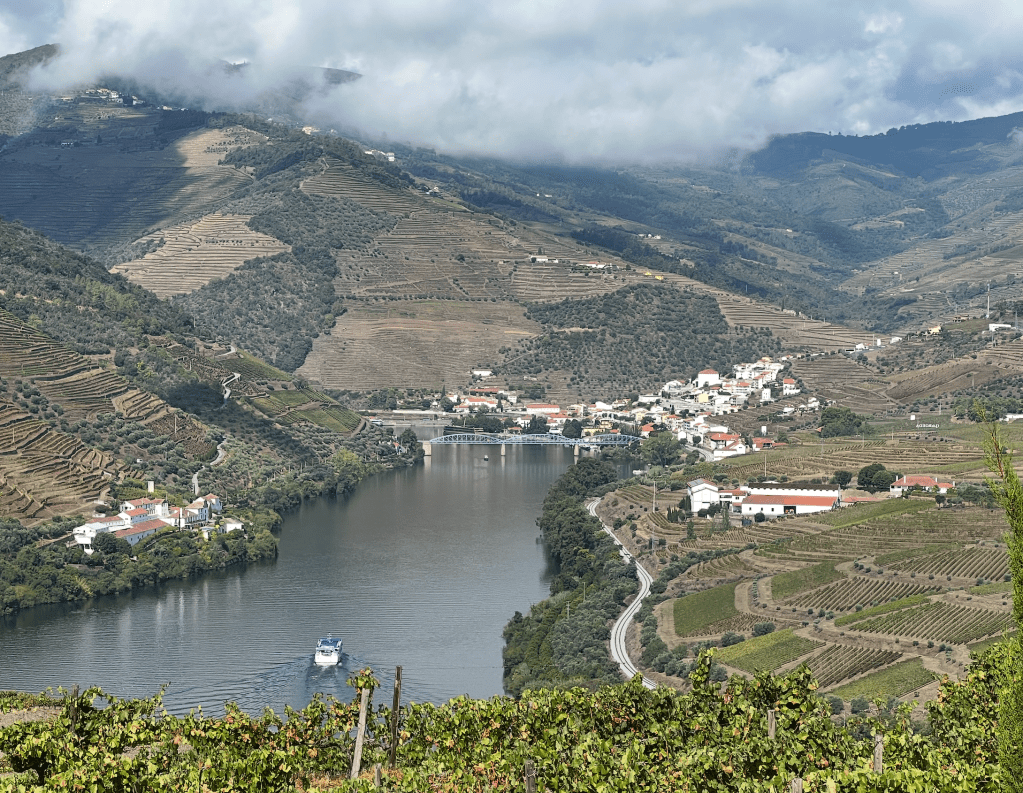

Day trips

There are several historical towns on the outskirts of Lisbon that are well worth visiting. Sintra, once the summer residence of the Portuguese kings, is a fairy-tale village crowned by a Moorish castle and dotted with several enchanting palaces. Queluz offers a graceful palace with elegant gardens inspired by Versailles.

Mafra stands on a grander scale. This vast convent, built with the wealth of Portugal’s maritime empire, houses one of the world’s most beautiful libraries. The convent’s construction inspired José Saramago’s celebrated novel Baltasar and Blimunda, published in 1982—a book that will enrich any visit to Mafra.

And then there is Óbidos, a perfectly preserved medieval town, offered by King Dom Dinis to his bride, Isabel of Aragon.